Python (programming language)

Python is a high-level, general-purpose programming language. Its design philosophy emphasizes code readability with the use of significant indentation.[31]

Python is dynamically typed and garbage-collected. It supports multiple programming paradigms, including structured (particularly procedural), object-oriented and functional programming. It is often described as a "batteries included" language due to its comprehensive standard library.[32][33]

Guido van Rossum began working on Python in the late 1980s as a successor to the ABC programming language and first released it in 1991 as Python 0.9.0.[34] Python 2.0 was released in 2000. Python 3.0, released in 2008, was a major revision not completely backward-compatible with earlier versions. Python 2.7.18, released in 2020, was the last release of Python 2.[35]

Python consistently ranks as one of the most popular programming languages, and has gained widespread use in the machine learning community.[36][37][38][39]

History

Python was conceived in the late 1980s[40] by Guido van Rossum at Centrum Wiskunde & Informatica (CWI) in the Netherlands as a successor to the ABC programming language, which was inspired by SETL,[41] capable of exception handling and interfacing with the Amoeba operating system.[10] Its implementation began in December 1989.[42] Van Rossum shouldered sole responsibility for the project, as the lead developer, until 12 July 2018, when he announced his "permanent vacation" from his responsibilities as Python's "benevolent dictator for life", a title the Python community bestowed upon him to reflect his long-term commitment as the project's chief decision-maker.[43] In January 2019, active Python core developers elected a five-member Steering Council to lead the project.[44][45]

Python 2.0 was released on 16 October 2000, with many major new features such as list comprehensions, cycle-detecting garbage collection, reference counting, and Unicode support.[46] Python 3.0, released on 3 December 2008, with many of its major features backported to Python 2.6.x[47] and 2.7.x. Releases of Python 3 include the 2to3 utility, which automates the translation of Python 2 code to Python 3.[48]

Python 2.7's end-of-life was initially set for 2015, then postponed to 2020 out of concern that a large body of existing code could not easily be forward-ported to Python 3.[49][50] No further security patches or other improvements will be released for it.[51][52] Currently only 3.8 and later are supported (2023 security issues were fixed in e.g. 3.7.17, the final 3.7.x release[53]). While Python 2.7 and older is officially unsupported, a different unofficial Python implementation, PyPy, continues to support Python 2, i.e. "2.7.18+" (plus 3.9 and 3.10), with the plus meaning (at least some) "backported security updates".[54]

In 2021 (and again twice in 2022), security updates were expedited, since all Python versions were insecure (including 2.7[55]) because of security issues leading to possible remote code execution[56] and web-cache poisoning.[57] In 2022, Python 3.10.4 and 3.9.12 were expedited[58] and 3.8.13, because of many security issues.[59] When Python 3.9.13 was released in May 2022, it was announced that the 3.9 series (joining the older series 3.8 and 3.7) would only receive security fixes in the future.[60] On 7 September 2022, four new releases were made due to a potential denial-of-service attack: 3.10.7, 3.9.14, 3.8.14, and 3.7.14.[61][62]

(As of October 2023) Python 3.12 is the stable release, and 3.12 and 3.11 are the only versions with active (as opposed to just security) support. Notable changes in 3.11 from 3.10 include increased program execution speed and improved error reporting.[63]

Python 3.12 adds syntax (and in fact every Python since at least 3.5 adds some syntax) to the language, the new (soft) keyword type (recent releases have added a lot of typing support e.g. new type union operator in 3.10), and 3.11 for exception handling, and 3.10 the match and case (soft) keywords, for structural pattern matching statements. Python 3.12 also drops outdated modules and functionality, and future versions will too, see below in Development section.

Python 3.11 claims to be between 10 and 60% faster than Python 3.10, and Python 3.12 adds another 5% on top of that. It also has improved error messages, and many other changes.

(As of June 2023), Python 3.8 is the oldest supported version of Python (albeit in the 'security support' phase), due to Python 3.7 reaching end-of-life.[64]

Design philosophy and features

Python is a multi-paradigm programming language. Object-oriented programming and structured programming are fully supported, and many of their features support functional programming and aspect-oriented programming (including metaprogramming[65] and metaobjects).[66] Many other paradigms are supported via extensions, including design by contract[67][68] and logic programming.[69]

Python uses dynamic typing and a combination of reference counting and a cycle-detecting garbage collector for memory management.[70] It uses dynamic name resolution (late binding), which binds method and variable names during program execution.

Its design offers some support for functional programming in the Lisp tradition. It has Template:Codes functions; list comprehensions, dictionaries, sets, and generator expressions.[71] The standard library has two modules (Template:Codes and Template:Codes) that implement functional tools borrowed from Haskell and Standard ML.[72]

Its core philosophy is summarized in the Zen of Python (PEP 20), which includes aphorisms such as:[73]

- Beautiful is better than ugly.

- Explicit is better than implicit.

- Simple is better than complex.

- Complex is better than complicated.

- Readability counts.

Rather than building all of its functionality into its core, Python was designed to be highly extensible via modules. This compact modularity has made it particularly popular as a means of adding programmable interfaces to existing applications. Van Rossum's vision of a small core language with a large standard library and easily extensible interpreter stemmed from his frustrations with ABC, which espoused the opposite approach.[40]

Python strives for a simpler, less-cluttered syntax and grammar while giving developers a choice in their coding methodology. In contrast to Perl's "there is more than one way to do it" motto, Python embraces a "there should be one—and preferably only one—obvious way to do it" philosophy.[73] Alex Martelli, a Fellow at the Python Software Foundation and Python book author, wrote: "To describe something as 'clever' is not considered a compliment in the Python culture."[74] One benefit of this approach is greater consistency across the Python user communities and shared understanding of the coding principles.

Python's developers usually strive to avoid premature optimization and reject patches to non-critical parts of the CPython reference implementation that would offer marginal increases in speed at the cost of clarity.[75] Execution speed can be improved by moving speed-critical functions to extension modules written in languages such as C, or by using a just-in-time compiler like PyPy. It is also possible to cross-compile to other languages, but it either doesn't provide the full speed-up that might be expected, since Python is a very dynamic language, or a restricted subset of Python is compiled, and possibly semantics are slightly changed.[76] Python's developers aim for it to be fun to use. This is reflected in its name—a tribute to the British comedy group Monty Python[77]—and in occasionally playful approaches to tutorials and reference materials, such as the use of the terms "spam" and "eggs" (a reference to a Monty Python sketch) in examples, instead of the often-used "foo" and "bar".[78][79]

A common neologism in the Python community is pythonic, which has a wide range of meanings related to program style. "Pythonic" code may use Python idioms well, be natural or show fluency in the language, or conform with Python's minimalist philosophy and emphasis on readability. Code that is difficult to understand or reads like a rough transcription from another programming language is called unpythonic.[80][81]

Syntax and semantics

Python is meant to be an easily readable language. Its formatting is visually uncluttered and often uses English keywords where other languages use punctuation. Unlike many other languages, it does not use curly brackets to delimit blocks, and semicolons after statements are allowed but rarely used. It has fewer syntactic exceptions and special cases than C or Pascal.[82]

Indentation

Python uses whitespace indentation, rather than curly brackets or keywords, to delimit blocks. An increase in indentation comes after certain statements; a decrease in indentation signifies the end of the current block.[83] Thus, the program's visual structure accurately represents its semantic structure.[84] This feature is sometimes termed the off-side rule. Some other languages use indentation this way; but in most, indentation has no semantic meaning. The recommended indent size is four spaces.[85]

Statements and control flow

Python's statements include:

- The assignment statement, using a single equals sign

= - The

ifstatement, which conditionally executes a block of code, along withelseandelif(a contraction of else-if) - The

forstatement, which iterates over an iterable object, capturing each element to a local variable for use by the attached block - The

whilestatement, which executes a block of code as long as its condition is true - The

trystatement, which allows exceptions raised in its attached code block to be caught and handled byexceptclauses (or new syntaxexcept*in Python 3.11 for exception groups[86]); it also ensures that clean-up code in afinallyblock is always run regardless of how the block exits - The

raisestatement, used to raise a specified exception or re-raise a caught exception - The

classstatement, which executes a block of code and attaches its local namespace to a class, for use in object-oriented programming - The

defstatement, which defines a function or method - The

withstatement, which encloses a code block within a context manager (for example, acquiring a lock before it is run, then releasing the lock; or opening and closing a file), allowing resource-acquisition-is-initialization (RAII)-like behavior and replacing a common try/finally idiom[87] - The

breakstatement, which exits a loop - The

continuestatement, which skips the rest of the current iteration and continues with the next - The

delstatement, which removes a variable—deleting the reference from the name to the value, and producing an error if the variable is referred to before it is redefined - The

passstatement, serving as a NOP, syntactically needed to create an empty code block - The

assertstatement, used in debugging to check for conditions that should apply - The

yieldstatement, which returns a value from a generator function (and also an operator); used to implement coroutines - The

returnstatement, used to return a value from a function - The

importandfromstatements, used to import modules whose functions or variables can be used in the current program

The assignment statement (=) binds a name as a reference to a separate, dynamically allocated object. Variables may subsequently be rebound at any time to any object. In Python, a variable name is a generic reference holder without a fixed data type; however, it always refers to some object with a type. This is called dynamic typing—in contrast to statically-typed languages, where each variable may contain only a value of a certain type.

Python does not support tail call optimization or first-class continuations, and, according to Van Rossum, it never will.[88][89] However, better support for coroutine-like functionality is provided by extending Python's generators.[90] Before 2.5, generators were lazy iterators; data was passed unidirectionally out of the generator. From Python 2.5 on, it is possible to pass data back into a generator function; and from version 3.3, it can be passed through multiple stack levels.[91]

Expressions

Python's expressions include:

- The

+,-, and*operators for mathematical addition, subtraction, and multiplication are similar to other languages, but the behavior of division differs. There are two types of divisions in Python: floor division (or integer division)//and floating-point/division.[92] Python uses the**operator for exponentiation. - Python uses the

+operator for string concatenation. Python uses the*operator for duplicating a string a specified number of times. - The

@infix operator. It is intended to be used by libraries such as NumPy for matrix multiplication.[93][94] - The syntax

:=, called the "walrus operator", was introduced in Python 3.8. It assigns values to variables as part of a larger expression.[95] - In Python,

==compares by value. Python'sisoperator may be used to compare object identities (comparison by reference), and comparisons may be chained—for example,a <= b <= c. - Python uses

and,or, andnotas Boolean operators. - Python has a type of expression called a list comprehension, as well as a more general expression called a generator expression.[71]

- Anonymous functions are implemented using lambda expressions; however, there may be only one expression in each body.

- Conditional expressions are written as

x if c else y[96] (different in order of operands from thec ? x : yoperator common to many other languages). - Python makes a distinction between lists and tuples. Lists are written as

[1, 2, 3], are mutable, and cannot be used as the keys of dictionaries (dictionary keys must be immutable in Python). Tuples, written as(1, 2, 3), are immutable and thus can be used as keys of dictionaries, provided all of the tuple's elements are immutable. The+operator can be used to concatenate two tuples, which does not directly modify their contents, but produces a new tuple containing the elements of both. Thus, given the variabletinitially equal to(1, 2, 3), executingt = t + (4, 5)first evaluatest + (4, 5), which yields(1, 2, 3, 4, 5), which is then assigned back tot—thereby effectively "modifying the contents" oftwhile conforming to the immutable nature of tuple objects. Parentheses are optional for tuples in unambiguous contexts.[97] - Python features sequence unpacking where multiple expressions, each evaluating to anything that can be assigned (to a variable, writable property, etc.) are associated in an identical manner to that forming tuple literals—and, as a whole, are put on the left-hand side of the equal sign in an assignment statement. The statement expects an iterable object on the right-hand side of the equal sign that produces the same number of values as the provided writable expressions; when iterated through them, it assigns each of the produced values to the corresponding expression on the left.[98]

- Python has a "string format" operator

%that functions analogously toprintfformat strings in C—e.g."spam=%s eggs=%d" % ("blah", 2)evaluates to"spam=blah eggs=2". In Python 2.6+ and 3+, this was supplemented by theformat()method of thestrclass, e.g."spam={0} eggs={1}".format("blah", 2). Python 3.6 added "f-strings":spam = "blah"; eggs = 2; f'spam={spam} eggs={eggs}'.[99] - Strings in Python can be concatenated by "adding" them (with the same operator as for adding integers and floats), e.g.

"spam" + "eggs"returns"spameggs". If strings contain numbers, they are added as strings rather than integers, e.g."2" + "2"returns"22". - Python has various string literals:

- Delimited by single or double quotes; unlike in Unix shells, Perl, and Perl-influenced languages, single and double quotes work the same. Both use the backslash (

\) as an escape character. String interpolation became available in Python 3.6 as "formatted string literals".[99] - Triple-quoted (beginning and ending with three single or double quotes), which may span multiple lines and function like here documents in shells, Perl, and Ruby.

- Raw string varieties, denoted by prefixing the string literal with

r. Escape sequences are not interpreted; hence raw strings are useful where literal backslashes are common, such as regular expressions and Windows-style paths. (Compare "@-quoting" in C#.)

- Delimited by single or double quotes; unlike in Unix shells, Perl, and Perl-influenced languages, single and double quotes work the same. Both use the backslash (

- Python has array index and array slicing expressions in lists, denoted as

a[key],a[start:stop]ora[start:stop:step]. Indexes are zero-based, and negative indexes are relative to the end. Slices take elements from the start index up to, but not including, the stop index. The third slice parameter called step or stride, allows elements to be skipped and reversed. Slice indexes may be omitted—for example,a[:]returns a copy of the entire list. Each element of a slice is a shallow copy.

In Python, a distinction between expressions and statements is rigidly enforced, in contrast to languages such as Common Lisp, Scheme, or Ruby. This leads to duplicating some functionality. For example:

- List comprehensions vs.

for-loops - Conditional expressions vs.

ifblocks - The

eval()vs.exec()built-in functions (in Python 2,execis a statement); the former is for expressions, the latter is for statements

Statements cannot be a part of an expression—so list and other comprehensions or lambda expressions, all being expressions, cannot contain statements. A particular case is that an assignment statement such as a = 1 cannot form part of the conditional expression of a conditional statement. This has the advantage of avoiding a classic C error of mistaking an assignment operator = for an equality operator == in conditions: if (c = 1) { ... } is syntactically valid (but probably unintended) C code, but if c = 1: ... causes a syntax error in Python.

Methods

Methods on objects are functions attached to the object's class; the syntax instance.method(argument) is, for normal methods and functions, syntactic sugar for Class.method(instance, argument). Python methods have an explicit self parameter to access instance data, in contrast to the implicit self (or this) in some other object-oriented programming languages (e.g., C++, Java, Objective-C, Ruby).[100] Python also provides methods, often called dunder methods (due to their names beginning and ending with double-underscores), to allow user-defined classes to modify how they are handled by native operations including length, comparison, in arithmetic operations and type conversion.[101]

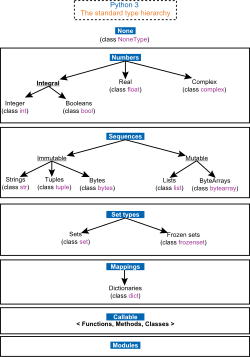

Typing

Python uses duck typing and has typed objects but untyped variable names. Type constraints are not checked at compile time; rather, operations on an object may fail, signifying that it is not of a suitable type. Despite being dynamically typed, Python is strongly typed, forbidding operations that are not well-defined (for example, adding a number to a string) rather than silently attempting to make sense of them.

Python allows programmers to define their own types using classes, most often used for object-oriented programming. New instances of classes are constructed by calling the class (for example, SpamClass() or EggsClass()), and the classes are instances of the metaclass type (itself an instance of itself), allowing metaprogramming and reflection.

Before version 3.0, Python had two kinds of classes (both using the same syntax): old-style and new-style,[102] current Python versions only support the semantics new style.

Python supports optional type annotations.[4][103] These annotations are not enforced by the language, but may be used by external tools such as mypy to catch errors.[104][105] Mypy also supports a Python compiler called mypyc, which leverages type annotations for optimization.[106]

| Type | Mutability | Description | Syntax examples |

|---|---|---|---|

bool

|

immutable | Boolean value | TrueFalse

|

bytearray

|

mutable | Sequence of bytes | bytearray(b'Some ASCII')bytearray(b"Some ASCII")bytearray([119, 105, 107, 105])

|

bytes

|

immutable | Sequence of bytes | b'Some ASCII'b"Some ASCII"bytes([119, 105, 107, 105])

|

complex

|

immutable | Complex number with real and imaginary parts | 3+2.7j3 + 2.7j

|

dict

|

mutable | Associative array (or dictionary) of key and value pairs; can contain mixed types (keys and values), keys must be a hashable type | {'key1': 1.0, 3: False}{}

|

types.EllipsisType

|

immutable | An ellipsis placeholder to be used as an index in NumPy arrays | ...Ellipsis

|

float

|

immutable | Double-precision floating-point number. The precision is machine-dependent but in practice is generally implemented as a 64-bit IEEE 754 number with 53 bits of precision.[107] |

|

frozenset

|

immutable | Unordered set, contains no duplicates; can contain mixed types, if hashable | frozenset([4.0, 'string', True])

|

int

|

immutable | Integer of unlimited magnitude[108] | 42

|

list

|

mutable | List, can contain mixed types | [4.0, 'string', True][]

|

types.NoneType

|

immutable | An object representing the absence of a value, often called null in other languages | None

|

types.NotImplementedType

|

immutable | A placeholder that can be returned from overloaded operators to indicate unsupported operand types. | NotImplemented

|

range

|

immutable | An immutable sequence of numbers commonly used for looping a specific number of times in for loops[109]

|

range(-1, 10)range(10, -5, -2)

|

set

|

mutable | Unordered set, contains no duplicates; can contain mixed types, if hashable | {4.0, 'string', True}set()

|

str

|

immutable | A character string: sequence of Unicode codepoints | 'Wikipedia'"Wikipedia""""Spanning multiple lines""" Spanning |

tuple

|

immutable | Can contain mixed types | (4.0, 'string', True)('single element',)()

|

Arithmetic operations

Python has the usual symbols for arithmetic operators (+, -, *, /), the floor division operator // and the modulo operation % (where the remainder can be negative, e.g. 4 % -3 == -2). It also has ** for exponentiation, e.g. 5**3 == 125 and 9**0.5 == 3.0, and a matrix‑multiplication operator @ .[110] These operators work like in traditional math; with the same precedence rules, the operators infix (+ and - can also be unary to represent positive and negative numbers respectively).

The division between integers produces floating-point results. The behavior of division has changed significantly over time:[111]

- Current Python (i.e. since 3.0) changed

/to always be floating-point division, e.g.5/2 == 2.5. - The floor division

//operator was introduced. So7//3 == 2,-7//3 == -3,7.5//3 == 2.0and-7.5//3 == -3.0. Addingfrom __future__ import divisioncauses a module used in Python 2.7 to use Python 3.0 rules for division (see above).

In Python terms, / is true division (or simply division), and // is floor division. / before version 3.0 is classic division.[111]

Rounding towards negative infinity, though different from most languages, adds consistency. For instance, it means that the equation (a + b)//b == a//b + 1 is always true. It also means that the equation b*(a//b) + a%b == a is valid for both positive and negative values of a. However, maintaining the validity of this equation means that while the result of a%b is, as expected, in the half-open interval [0, b), where b is a positive integer, it has to lie in the interval (b, 0] when b is negative.[112]

Python provides a round function for rounding a float to the nearest integer. For tie-breaking, Python 3 uses round to even: round(1.5) and round(2.5) both produce 2.[113] Versions before 3 used round-away-from-zero: round(0.5) is 1.0, round(-0.5) is −1.0.[114]

Python allows Boolean expressions with multiple equality relations in a manner that is consistent with general use in mathematics. For example, the expression a < b < c tests whether a is less than b and b is less than c.[115] C-derived languages interpret this expression differently: in C, the expression would first evaluate a < b, resulting in 0 or 1, and that result would then be compared with c.[116]

Python uses arbitrary-precision arithmetic for all integer operations. The Decimal type/class in the decimal module provides decimal floating-point numbers to a pre-defined arbitrary precision and several rounding modes.[117] The Fraction class in the fractions module provides arbitrary precision for rational numbers.[118]

Due to Python's extensive mathematics library, and the third-party library NumPy that further extends the native capabilities, it is frequently used as a scientific scripting language to aid in problems such as numerical data processing and manipulation.[119][120]

Programming examples

Hello world program:

print('Hello, world!')

Program to calculate the factorial of a positive integer:

n = int(input('Type a number, and its factorial will be printed: '))

if n < 0:

raise ValueError('You must enter a non-negative integer')

factorial = 1

for i in range(2, n + 1):

factorial *= i

print(factorial)

Libraries

Python's large standard library[121] provides tools suited to many tasks and is commonly cited as one of its greatest strengths. For Internet-facing applications, many standard formats and protocols such as MIME and HTTP are supported. It includes modules for creating graphical user interfaces, connecting to relational databases, generating pseudorandom numbers, arithmetic with arbitrary-precision decimals,[122] manipulating regular expressions, and unit testing.

Some parts of the standard library are covered by specifications—for example, the Web Server Gateway Interface (WSGI) implementation wsgiref follows PEP 333[123]—but most are specified by their code, internal documentation, and test suites. However, because most of the standard library is cross-platform Python code, only a few modules need altering or rewriting for variant implementations.

(As of November 2022) the Python Package Index (PyPI), the official repository for third-party Python software, contains over 415,000[124] packages with a wide range of functionality, including:

Development environments

Most Python implementations (including CPython) include a read–eval–print loop (REPL), permitting them to function as a command line interpreter for which users enter statements sequentially and receive results immediately.

Python also comes with an Integrated development environment (IDE) called IDLE, which is more beginner-oriented.

Other shells, including IDLE and IPython, add further abilities such as improved auto-completion, session state retention, and syntax highlighting.

As well as standard desktop integrated development environments including PyCharm, IntelliJ Idea, Visual Studio Code etc, there are web browser-based IDEs, including SageMath, for developing science- and math-related programs; PythonAnywhere, a browser-based IDE and hosting environment; and Canopy IDE, a commercial IDE emphasizing scientific computing.[125]

Implementations

Reference implementation

CPython is the reference implementation of Python. It is written in C, meeting the C89 standard (Python 3.11 uses C11[126]) with several select C99 features. CPython includes its own C extensions, but third-party extensions are not limited to older C versions—e.g. they can be implemented with C11 or C++.[127][128]) It compiles Python programs into an intermediate bytecode[129] which is then executed by its virtual machine.[130] CPython is distributed with a large standard library written in a mixture of C and native Python, and is available for many platforms, including Windows (starting with Python 3.9, the Python installer deliberately fails to install on Windows 7 and 8;[131][132] Windows XP was supported until Python 3.5) and most modern Unix-like systems, including macOS (and Apple M1 Macs, since Python 3.9.1, with experimental installer) and unofficial support for e.g. VMS.[133] Platform portability was one of its earliest priorities.[134] (During Python 1 and 2 development, even OS/2 and Solaris were supported,[135] but support has since been dropped for many platforms.)

Other implementations

- PyPy is a fast, compliant interpreter of Python 2.7 and 3.8.[136][137] Its just-in-time compiler often brings a significant speed improvement over CPython but some libraries written in C cannot be used with it.[138]

- Stackless Python is a significant fork of CPython that implements microthreads; it does not use the call stack in the same way, thus allowing massively concurrent programs. PyPy also has a stackless version.[139]

- MicroPython and CircuitPython are Python 3 variants optimized for microcontrollers, including Lego Mindstorms EV3.[140]

- Pyston is a variant of the Python runtime that uses just-in-time compilation to speed up the execution of Python programs.[141]

- Cinder is a performance-oriented fork of CPython 3.8 that contains a number of optimizations, including bytecode inline caching, eager evaluation of coroutines, a method-at-a-time JIT, and an experimental bytecode compiler.[142]

- Snek[143][144][145] Embedded Computing Language (supporting e.g. 8-bit AVR microcontrollers such as ATmega 328P-based Arduino, and larger ones that are MicroPython can also support) "is Python-inspired, but it is not Python. It is possible to write Snek programs that run under a full Python system, but most Python programs will not run under Snek." It's an imperative language not including OOP/classes unlike Python, and simplifying to one number type (like JavaScript, except using smaller) 32-bit single-precision "Integer values of less than 24 bits can be represented exactly in these floating point values".[146]

Unsupported implementations

Other just-in-time Python compilers have been developed, but are now unsupported:

- Google began a project named Unladen Swallow in 2009, with the aim of speeding up the Python interpreter fivefold by using the LLVM, and of improving its multithreading ability to scale to thousands of cores,[147] while ordinary implementations suffer from the global interpreter lock.

- Psyco is a discontinued just-in-time specializing compiler that integrates with CPython and transforms bytecode to machine code at runtime. The emitted code is specialized for certain data types and is faster than the standard Python code. Psyco does not support Python 2.7 or later.

- PyS60 was a Python 2 interpreter for Series 60 mobile phones released by Nokia in 2005. It implemented many of the modules from the standard library and some additional modules for integrating with the Symbian operating system. The Nokia N900 also supports Python with GTK widget libraries, enabling programs to be written and run on the target device.[148]

Cross-compilers to other languages

There are several compilers/transpilers to high-level object languages, with either unrestricted Python, a restricted subset of Python, or a language similar to Python as the source language:

- Brython,[149] Transcrypt[150][151] and Pyjs (latest release in 2012) compile Python to JavaScript.

- Codon compiles a subset of statically typed Python[152] to machine code (via LLVM) and supports native multithreading.[153]

- Cython compiles (a superset of) Python to C. The resulting code is also usable with Python via direct C-level API calls into the Python interpreter.

- PyJL compiles/transpiles a subset of Python to "human-readable, maintainable, and high-performance Julia source code".[76] Despite claiming high performance, no tool can claim to do that for arbitrary Python code; i.e. it's known not possible to compile to a faster language or machine code. Unless semantics of Python are changed, but in many cases speedup is possible with few or no changes in the Python code. The faster Julia source code can then be used from Python, or compiled to machine code, and based that way.

- Nuitka compiles Python into C.[154]

- Numba uses LLVM to compile a subset of Python to machine code.

- Pythran compiles a subset of Python 3 to C++ (C++11).[155]

- RPython can be compiled to C, and is used to build the PyPy interpreter of Python.

- The Python → 11l → C++ transpiler[156] compiles a subset of Python 3 to C++ (C++17).

Specialized:

- MyHDL is a Python-based hardware description language (HDL), that converts MyHDL code to Verilog or VHDL code.

Older projects (or not to be used with Python 3.x and latest syntax):

- Google's Grumpy (latest release in 2017) transpiles Python 2 to Go.[157][158][159]

- IronPython allows running Python 2.7 programs (and an alpha, released in 2021, is also available for "Python 3.4, although features and behaviors from later versions may be included"[160]) on the .NET Common Language Runtime.[161]

- Jython compiles Python 2.7 to Java bytecode, allowing the use of the Java libraries from a Python program.[162]

- Pyrex (latest release in 2010) and Shed Skin (latest release in 2013) compile to C and C++ respectively.

Performance

Performance comparison of various Python implementations on a non-numerical (combinatorial) workload was presented at EuroSciPy '13.[163] Python's performance compared to other programming languages is also benchmarked by The Computer Language Benchmarks Game.[164]

Development

Python's development is conducted largely through the Python Enhancement Proposal (PEP) process, the primary mechanism for proposing major new features, collecting community input on issues, and documenting Python design decisions.[165] Python coding style is covered in PEP 8.[166] Outstanding PEPs are reviewed and commented on by the Python community and the steering council.[165]

Enhancement of the language corresponds with the development of the CPython reference implementation. The mailing list python-dev is the primary forum for the language's development. Specific issues were originally discussed in the Roundup bug tracker hosted at by the foundation.[167] In 2022, all issues and discussions were migrated to GitHub.[168] Development originally took place on a self-hosted source-code repository running Mercurial, until Python moved to GitHub in January 2017.[169]

CPython's public releases come in three types, distinguished by which part of the version number is incremented:

- Backward-incompatible versions, where code is expected to break and needs to be manually ported. The first part of the version number is incremented. These releases happen infrequently—version 3.0 was released 8 years after 2.0. According to Guido van Rossum, a version 4.0 is very unlikely to ever happen.[170]

- Major or "feature" releases are largely compatible with the previous version but introduce new features. The second part of the version number is incremented. Starting with Python 3.9, these releases are expected to happen annually.[171][172] Each major version is supported by bug fixes for several years after its release.[173]

- Bugfix releases,[174] which introduce no new features, occur about every 3 months and are made when a sufficient number of bugs have been fixed upstream since the last release. Security vulnerabilities are also patched in these releases. The third and final part of the version number is incremented.[174]

Many alpha, beta, and release-candidates are also released as previews and for testing before final releases. Although there is a rough schedule for each release, they are often delayed if the code is not ready. Python's development team monitors the state of the code by running the large unit test suite during development.[175]

The major academic conference on Python is PyCon. There are also special Python mentoring programs, such as PyLadies.

Python 3.12 removed wstr meaning Python extensions[176] need to be modified,[177] and 3.10 added pattern matching to the language.[178]

Python 3.12 dropped some outdated modules, and more will be dropped in the future, deprecated as of 3.13; already deprecated array 'u' format code will emit DeprecationWarning since 3.13 and will be removed in Python 3.16. The 'w' format code should be used instead. Part of ctypes is also deprecated and http.server.CGIHTTPRequestHandler will emit a DeprecationWarning, and will be removed in 3.15. Using that code already has a high potential for both security and functionality bugs. Parts of the typing module are deprecated, e.g. creating a typing.NamedTuple class using keyword arguments to denote the fields and such (and more) will be disallowed in Python 3.15.

API documentation generators

Tools that can generate documentation for Python API include pydoc (available as part of the standard library), Sphinx, Pdoc and its forks, Doxygen and Graphviz, among others.[179]

Naming

Python's name is derived from the British comedy group Monty Python, whom Python creator Guido van Rossum enjoyed while developing the language. Monty Python references appear frequently in Python code and culture;[180] for example, the metasyntactic variables often used in Python literature are spam and eggs instead of the traditional foo and bar.[180][181] The official Python documentation also contains various references to Monty Python routines.[182][183] Users of Python are sometimes referred to as "Pythonistas".[184]

The prefix Py- is used to show that something is related to Python. Examples of the use of this prefix in names of Python applications or libraries include Pygame, a binding of SDL to Python (commonly used to create games); PyQt and PyGTK, which bind Qt and GTK to Python respectively; and PyPy, a Python implementation originally written in Python.

Popularity

Since 2003, Python has consistently ranked in the top ten most popular programming languages in the TIOBE Programming Community Index where (As of December 2022) it was the most popular language (ahead of C, C++, and Java).[38] It was selected Programming Language of the Year (for "the highest rise in ratings in a year") in 2007, 2010, 2018, and 2020 (the only language to have done so four times (As of 2020)[185]).

An empirical study found that scripting languages, such as Python, are more productive than conventional languages, such as C and Java, for programming problems involving string manipulation and search in a dictionary, and determined that memory consumption was often "better than Java and not much worse than C or C++".[186]

Large organizations that use Python include Wikipedia, Google,[187] Yahoo!,[188] CERN,[189] NASA,[190] Facebook,[191] Amazon, Instagram,[192] Spotify,[193] and some smaller entities like ILM[194] and ITA.[195] The social news networking site Reddit was written mostly in Python.[196]

Uses

Python can serve as a scripting language for web applications, e.g. via mod wsgi for the Apache webserver.[197] With Web Server Gateway Interface, a standard API has evolved to facilitate these applications. Web frameworks like Django, Pylons, Pyramid, TurboGears, web2py, Tornado, Flask, Bottle, and Zope support developers in the design and maintenance of complex applications. Pyjs and IronPython can be used to develop the client-side of Ajax-based applications. SQLAlchemy can be used as a data mapper to a relational database. Twisted is a framework to program communications between computers, and is used (for example) by Dropbox.

Libraries such as NumPy, SciPy, and Matplotlib allow the effective use of Python in scientific computing,[198][199] with specialized libraries such as Biopython and Astropy providing domain-specific functionality. SageMath is a computer algebra system with a notebook interface programmable in Python: its library covers many aspects of mathematics, including algebra, combinatorics, numerical mathematics, number theory, and calculus.[200] OpenCV has Python bindings with a rich set of features for computer vision and image processing.[201]

Python is commonly used in artificial intelligence projects and machine learning projects with the help of libraries like TensorFlow, Keras, Pytorch, and scikit-learn.[202][203][204][205] As a scripting language with a modular architecture, simple syntax, and rich text processing tools, Python is often used for natural language processing.[206]

Python can also be used for graphical user interface (GUI) by using libraries like Tkinter.[207][208]

Python can also be used to create games, with libraries such as Pygame, which can make 2D games.

Python has been successfully embedded in many software products as a scripting language, including in finite element method software such as Abaqus, 3D parametric modelers like FreeCAD, 3D animation packages such as 3ds Max, Blender, Cinema 4D, Lightwave, Houdini, Maya, modo, MotionBuilder, Softimage, the visual effects compositor Nuke, 2D imaging programs like GIMP,[209] Inkscape, Scribus and Paint Shop Pro,[210] and musical notation programs like scorewriter and capella. GNU Debugger uses Python as a pretty printer to show complex structures such as C++ containers. Esri promotes Python as the best choice for writing scripts in ArcGIS.[211] It has also been used in several video games,[212][213] and has been adopted as first of the three available programming languages in Google App Engine, the other two being Java and Go.[214]

Many operating systems include Python as a standard component. It ships with most Linux distributions,[215] AmigaOS 4 (using Python 2.7), FreeBSD (as a package), NetBSD, and OpenBSD (as a package) and can be used from the command line (terminal). Many Linux distributions use installers written in Python: Ubuntu uses the Ubiquity installer, while Red Hat Linux and Fedora Linux use the Anaconda installer. Gentoo Linux uses Python in its package management system, Portage.

Python is used extensively in the information security industry, including in exploit development.[216][217]

Most of the Sugar software for the One Laptop per Child XO, developed at Sugar Labs (As of 2008), is written in Python.[218] The Raspberry Pi single-board computer project has adopted Python as its main user-programming language.

LibreOffice includes Python and intends to replace Java with Python. Its Python Scripting Provider is a core feature[219] since Version 4.0 from 7 February 2013.

Languages influenced by Python

Python's design and philosophy have influenced many other programming languages:

- Boo uses indentation, a similar syntax, and a similar object model.[220]

- Cobra uses indentation and a similar syntax, and its Acknowledgements document lists Python first among languages that influenced it.[221]

- CoffeeScript, a programming language that cross-compiles to JavaScript, has Python-inspired syntax.

- ECMAScript/JavaScript borrowed iterators and generators from Python.[222]

- GDScript, a scripting language very similar to Python, built-in to the Godot game engine.[223]

- Go is designed for the "speed of working in a dynamic language like Python"[224] and shares the same syntax for slicing arrays.

- Groovy was motivated by the desire to bring the Python design philosophy to Java.[225]

- Julia was designed to be "as usable for general programming as Python".[26]

- Mojo is currently a non-strict[27][226] (aims to be a strict) superset of Python (e.g. still missing classes, and adding e.g. struct), and is up to 35,000x faster[227][better source needed] for some code (mandelbrot, since it is embarrassingly parallel), where static typing helps (and MLIR it is implemented with), and, e.g. 4000 times faster for matrix multiplication.

- Nim uses indentation and similar syntax.[228]

- Ruby's creator, Yukihiro Matsumoto, has said: "I wanted a scripting language that was more powerful than Perl, and more object-oriented than Python. That's why I decided to design my own language."[229]

- Swift, a programming language developed by Apple, has some Python-inspired syntax.[230]

Python's development practices have also been emulated by other languages. For example, the practice of requiring a document describing the rationale for, and issues surrounding, a change to the language (in Python, a PEP) is also used in Tcl,[231] Erlang,[232] and Swift.[233]

See also

- Python syntax and semantics

- pip (package manager)

- List of programming languages

- History of programming languages

- Comparison of programming languages

References

- ↑ "General Python FAQ – Python 3.9.2 documentation". https://docs.python.org/3/faq/general.html#what-is-python.

- ↑ "Python 0.9.1 part 01/21". alt.sources archives. https://www.tuhs.org/Usenet/alt.sources/1991-February/001749.html.

- ↑ "Why is Python a dynamic language and also a strongly typed language". https://wiki.python.org/moin/Why%20is%20Python%20a%20dynamic%20language%20and%20also%20a%20strongly%20typed%20language.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "PEP 483 – The Theory of Type Hints". https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0483/.

- ↑ "test – Regression tests package for Python – Python 3.7.13 documentation". https://docs.python.org/3.7/library/test.html?highlight=android#test.support.is_android.

- ↑ "platform – Access to underlying platform's identifying data – Python 3.10.4 documentation". https://docs.python.org/3/library/platform.html?highlight=android.

- ↑ "Download Python for Other Platforms" (in en). https://www.python.org/download/other/.

- ↑ Holth, Moore (30 March 2014). "PEP 0441 – Improving Python ZIP Application Support". https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0441/.

- ↑ "Starlark Language". https://docs.bazel.build/versions/master/skylark/language.html.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Why was Python created in the first place?". General Python FAQ. Python Software Foundation. https://docs.python.org/faq/general.html#why-was-python-created-in-the-first-place. "I had extensive experience with implementing an interpreted language in the ABC group at CWI, and from working with this group I had learned a lot about language design. This is the origin of many Python features, including the use of indentation for statement grouping and the inclusion of very high-level data types (although the details are all different in Python)."

- ↑ "Ada 83 Reference Manual (raise statement)". http://archive.adaic.com/standards/83lrm/html/lrm-11-03.html#11.3.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Kuchling, Andrew M. (22 December 2006). "Interview with Guido van Rossum (July 1998)". amk.ca. http://www.amk.ca/python/writing/gvr-interview. "I'd spent a summer at DEC's Systems Research Center, which introduced me to Modula-2+; the Modula-3 final report was being written there at about the same time. What I learned there later showed up in Python's exception handling, modules, and the fact that methods explicitly contain 'self' in their parameter list. String slicing came from Algol-68 and Icon."

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "itertools – Functions creating iterators for efficient looping – Python 3.7.1 documentation". https://docs.python.org/3/library/itertools.html. "This module implements a number of iterator building blocks inspired by constructs from APL, Haskell, and SML."

- ↑ van Rossum, Guido (1993). "An Introduction to Python for UNIX/C Programmers". Proceedings of the NLUUG Najaarsconferentie (Dutch UNIX Users Group). "even though the design of C is far from ideal, its influence on Python is considerable.".

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Classes". The Python Tutorial. Python Software Foundation. https://docs.python.org/tutorial/classes.html. "It is a mixture of the class mechanisms found in C++ and Modula-3"

- ↑ Lundh, Fredrik. "Call By Object". effbot.org. http://effbot.org/zone/call-by-object.htm. "replace "CLU" with "Python", "record" with "instance", and "procedure" with "function or method", and you get a pretty accurate description of Python's object model."

- ↑ Simionato, Michele. "The Python 2.3 Method Resolution Order". Python Software Foundation. https://www.python.org/download/releases/2.3/mro/. "The C3 method itself has nothing to do with Python, since it was invented by people working on Dylan and it is described in a paper intended for lispers"

- ↑ Kuchling, A. M.. "Functional Programming HOWTO". Python v2.7.2 documentation. Python Software Foundation. https://docs.python.org/howto/functional.html. "List comprehensions and generator expressions [...] are a concise notation for such operations, borrowed from the functional programming language Haskell."

- ↑ Schemenauer, Neil; Peters, Tim; Hetland, Magnus Lie (18 May 2001). "PEP 255 – Simple Generators". Python Enhancement Proposals. Python Software Foundation. https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0255/.

- ↑ "More Control Flow Tools". Python 3 documentation. Python Software Foundation. https://docs.python.org/3.2/tutorial/controlflow.html. "By popular demand, a few features commonly found in functional programming languages like Lisp have been added to Python. With the lambda keyword, small anonymous functions can be created."

- ↑ "re – Regular expression operations – Python 3.10.6 documentation". https://docs.python.org/3/library/re.html. "This module provides regular expression matching operations similar to those found in Perl."

- ↑ "CoffeeScript". https://coffeescript.org/.

- ↑ "The Genie Programming Language Tutorial". https://wiki.gnome.org/action/show/Projects/Genie.

- ↑ "Perl and Python influences in JavaScript". 24 February 2013. http://www.2ality.com/2013/02/javascript-influences.html.

- ↑ Rauschmayer, Axel. "Chapter 3: The Nature of JavaScript; Influences". http://speakingjs.com/es5/ch03.html.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Why We Created Julia". February 2012. https://julialang.org/blog/2012/02/why-we-created-julia. "We want something as usable for general programming as Python [...]"

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Krill, Paul (2023-05-04). "Mojo language marries Python and MLIR for AI development" (in en). https://www.infoworld.com/article/3695588/mojo-language-marries-python-and-mlir-for-ai-development.html.

- ↑ Ring Team (4 December 2017). "Ring and other languages". ring-lang.net. ring-lang. http://ring-lang.sourceforge.net/doc1.6/introduction.html#ring-and-other-languages.

- ↑ Bini, Ola (2007). Practical JRuby on Rails Web 2.0 Projects: bringing Ruby on Rails to the Java platform. Berkeley: APress. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-59059-881-8. https://archive.org/details/practicaljrubyon0000bini/page/3.

- ↑ Lattner, Chris (3 June 2014). "Chris Lattner's Homepage". Chris Lattner. http://nondot.org/sabre/. "The Swift language is the product of tireless effort from a team of language experts, documentation gurus, compiler optimization ninjas, and an incredibly important internal dogfooding group who provided feedback to help refine and battle-test ideas. Of course, it also greatly benefited from the experiences hard-won by many other languages in the field, drawing ideas from Objective-C, Rust, Haskell, Ruby, Python, C#, CLU, and far too many others to list."

- ↑ Kuhlman, Dave. "A Python Book: Beginning Python, Advanced Python, and Python Exercises". Section 1.1. https://www.davekuhlman.org/python_book_01.pdf.

- ↑ "About Python". Python Software Foundation. https://www.python.org/about., second section "Fans of Python use the phrase "batteries included" to describe the standard library, which covers everything from asynchronous processing to zip files."

- ↑ "PEP 206 – Python Advanced Library". https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0206/.

- ↑ Rossum, Guido Van (2009-01-20). "The History of Python: A Brief Timeline of Python". https://python-history.blogspot.com/2009/01/brief-timeline-of-python.html.

- ↑ Peterson, Benjamin (20 April 2020). "Python Insider: Python 2.7.18, the last release of Python 2". https://pythoninsider.blogspot.com/2020/04/python-2718-last-release-of-python-2.html.

- ↑ "Stack Overflow Developer Survey 2022" (in en). https://survey.stackoverflow.co/2022/.

- ↑ "The State of Developer Ecosystem in 2020 Infographic" (in en). https://www.jetbrains.com/lp/devecosystem-2020/.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "TIOBE Index". TIOBE. https://www.tiobe.com/tiobe-index/. "The TIOBE Programming Community index is an indicator of the popularity of programming languages" Updated as required.

- ↑ "PYPL PopularitY of Programming Language index" (in en). https://pypl.github.io/PYPL.html.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Venners, Bill (13 January 2003). "The Making of Python". Artima Developer. Artima. http://www.artima.com/intv/pythonP.html.

- ↑ van Rossum, Guido (29 August 2000). "SETL (was: Lukewarm about range literals)". Python-Dev (Mailing list). Archived from the original on 14 July 2018. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ↑ van Rossum, Guido (20 January 2009). "A Brief Timeline of Python". The History of Python. https://python-history.blogspot.com/2009/01/brief-timeline-of-python.html.

- ↑ Fairchild, Carlie (12 July 2018). "Guido van Rossum Stepping Down from Role as Python's Benevolent Dictator For Life". Linux Journal. https://www.linuxjournal.com/content/guido-van-rossum-stepping-down-role-pythons-benevolent-dictator-life. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ↑ "PEP 8100". Python Software Foundation. https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-8100/.

- ↑ "PEP 13 – Python Language Governance" (in en). https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0013/.

- ↑ Kuchling, A. M.; Zadka, Moshe (16 October 2000). "What's New in Python 2.0". Python Software Foundation. https://docs.python.org/whatsnew/2.0.html.

- ↑ van Rossum, Guido (5 April 2006). "PEP 3000 – Python 3000". Python Enhancement Proposals. Python Software Foundation. https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-3000/.

- ↑ "2to3 – Automated Python 2 to 3 code translation". https://docs.python.org/3/library/2to3.html.

- ↑ "PEP 373 – Python 2.7 Release Schedule". python.org. https://legacy.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0373/.

- ↑ "PEP 466 – Network Security Enhancements for Python 2.7.x". python.org. https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0466/.

- ↑ "Sunsetting Python 2" (in en). https://www.python.org/doc/sunset-python-2/.

- ↑ "PEP 373 – Python 2.7 Release Schedule" (in en). https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0373/.

- ↑ "Python Release Python 3.7.17" (in en). https://www.python.org/downloads/release/python-3717/.

- ↑ mattip (2023-12-25). "PyPy v7.3.14 release" (in en). https://www.pypy.org/posts/2023/12/pypy-v7314-release.html.

- ↑ "Red Hat Customer Portal – Access to 24x7 support and knowledge". https://access.redhat.com/security/cve/cve-2021-3177.

- ↑ "CVE – CVE-2021-3177". https://cve.mitre.org/cgi-bin/cvename.cgi?name=CVE-2021-3177.

- ↑ "CVE – CVE-2021-23336". https://cve.mitre.org/cgi-bin/cvename.cgi?name=CVE-2021-23336.

- ↑ Langa, Łukasz (2022-03-24). "Python Insider: Python 3.10.4 and 3.9.12 are now available out of schedule". https://pythoninsider.blogspot.com/2022/03/python-3104-and-3912-are-now-available.html.

- ↑ Langa, Łukasz (2022-03-16). "Python Insider: Python 3.10.3, 3.9.11, 3.8.13, and 3.7.13 are now available with security content". https://pythoninsider.blogspot.com/2022/03/python-3103-3911-3813-and-3713-are-now.html.

- ↑ Langa, Łukasz (2022-05-17). "Python Insider: Python 3.9.13 is now available". https://pythoninsider.blogspot.com/2022/05/python-3913-is-now-available.html.

- ↑ "Python Insider: Python releases 3.10.7, 3.9.14, 3.8.14, and 3.7.14 are now available". pythoninsider.blogspot.com. 7 September 2022. https://pythoninsider.blogspot.com/2022/09/python-releases-3107-3914-3814-and-3714.html.

- ↑ "CVE - CVE-2020-10735". cve.mitre.org. https://cve.mitre.org/cgi-bin/cvename.cgi?name=CVE-2020-10735.

- ↑ corbet (24 October 2022). "Python 3.11 released [LWN.net"]. lwn.net. https://lwn.net/Articles/912216/.

- ↑ "Python" (in en-US). 2023-08-10. https://endoflife.date/python.

- ↑ The Cain Gang Ltd.. "Python Metaclasses: Who? Why? When?". https://www.python.org/community/pycon/dc2004/papers/24/metaclasses-pycon.pdf.

- ↑ "3.3. Special method names". The Python Language Reference. Python Software Foundation. https://docs.python.org/3.0/reference/datamodel.html#special-method-names.

- ↑ "PyDBC: method preconditions, method postconditions and class invariants for Python". http://www.nongnu.org/pydbc/.

- ↑ "Contracts for Python". http://www.wayforward.net/pycontract/.

- ↑ "PyDatalog". https://sites.google.com/site/pydatalog/.

- ↑ "Extending and Embedding the Python Interpreter: Reference Counts" (in en). Docs.python.org. https://docs.python.org/extending/extending.html#reference-counts. "Since Python makes heavy use of

malloc()andfree(), it needs a strategy to avoid memory leaks as well as the use of freed memory. The chosen method is called reference counting." - ↑ 71.0 71.1 Hettinger, Raymond (30 January 2002). "PEP 289 – Generator Expressions". Python Enhancement Proposals. Python Software Foundation. https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0289/.

- ↑ "6.5 itertools – Functions creating iterators for efficient looping". Docs.python.org. https://docs.python.org/3/library/itertools.html.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Peters, Tim (19 August 2004). "PEP 20 – The Zen of Python". Python Enhancement Proposals. Python Software Foundation. https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0020/.

- ↑ Martelli, Alex; Ravenscroft, Anna; Ascher, David (2005). Python Cookbook, 2nd Edition. O'Reilly Media. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-596-00797-3. http://shop.oreilly.com/product/9780596007973.do. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ↑ "Python Culture". January 21, 2014. http://ebeab.com/2014/01/21/python-culture/.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 "Transpiling Python to Julia using PyJL". https://web.ist.utl.pt/antonio.menezes.leitao/ADA/documents/publications_docs/2022_TranspilingPythonToJuliaUsingPyJL.pdf. "After manually modifying one line of code by specifying the necessary type information, we obtained a speedup of 52.6×, making the translated Julia code 19.5× faster than the original Python code."

- ↑ "Why is it called Python?". General Python FAQ. Docs.python.org. https://docs.python.org/3/faq/general.html#why-is-it-called-python.

- ↑ "15 Ways Python Is a Powerful Force on the Web". https://insidetech.monster.com/training/articles/8114-15-ways-python-is-a-powerful-force-on-the-web.

- ↑ "pprint – Data pretty printer – Python 3.11.0 documentation". https://docs.python.org/3/library/pprint.html. "stuff=['spam', 'eggs', 'lumberjack', 'knights', 'ni']"

- ↑ Clark, Robert (26 April 2019). "How to be Pythonic and why you should care". https://towardsdatascience.com/how-to-be-pythonic-and-why-you-should-care-188d63a5037e.

- ↑ "Code Style – The Hitchhiker's Guide to Python". https://docs.python-guide.org/writing/style.

- ↑ "Is Python a good language for beginning programmers?". General Python FAQ. Python Software Foundation. https://docs.python.org/faq/general.html#is-python-a-good-language-for-beginning-programmers.

- ↑ "Myths about indentation in Python". Secnetix.de. http://www.secnetix.de/~olli/Python/block_indentation.hawk.

- ↑ Guttag, John V. (12 August 2016). Introduction to Computation and Programming Using Python: With Application to Understanding Data. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-52962-4.

- ↑ "PEP 8 – Style Guide for Python Code". https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0008/.

- ↑ "8. Errors and Exceptions – Python 3.12.0a0 documentation". https://docs.python.org/3.11/tutorial/errors.html.

- ↑ "Highlights: Python 2.5". https://www.python.org/download/releases/2.5/highlights/.

- ↑ van Rossum, Guido (22 April 2009). "Tail Recursion Elimination". Neopythonic.blogspot.be. http://neopythonic.blogspot.be/2009/04/tail-recursion-elimination.html.

- ↑ van Rossum, Guido (9 February 2006). "Language Design Is Not Just Solving Puzzles". Artima forums. Artima. http://www.artima.com/weblogs/viewpost.jsp?thread=147358.

- ↑ van Rossum, Guido; Eby, Phillip J. (10 May 2005). "PEP 342 – Coroutines via Enhanced Generators". Python Enhancement Proposals. Python Software Foundation. https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0342/.

- ↑ "PEP 380". Python.org. https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0380/.

- ↑ "division". https://docs.python.org.

- ↑ "PEP 0465 – A dedicated infix operator for matrix multiplication". https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0465/.

- ↑ "Python 3.5.1 Release and Changelog". https://www.python.org/downloads/release/python-351/.

- ↑ "What's New in Python 3.8". https://docs.python.org/3.8/whatsnew/3.8.html.

- ↑ van Rossum, Guido; Hettinger, Raymond (7 February 2003). "PEP 308 – Conditional Expressions". Python Enhancement Proposals. Python Software Foundation. https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0308/.

- ↑ "4. Built-in Types – Python 3.6.3rc1 documentation". https://docs.python.org/3/library/stdtypes.html#tuple.

- ↑ "5.3. Tuples and Sequences – Python 3.7.1rc2 documentation". https://docs.python.org/3/tutorial/datastructures.html#tuples-and-sequences.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 "PEP 498 – Literal String Interpolation". https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0498/.

- ↑ "Why must 'self' be used explicitly in method definitions and calls?". Design and History FAQ. Python Software Foundation. https://docs.python.org/faq/design.html#why-must-self-be-used-explicitly-in-method-definitions-and-calls.

- ↑ Sweigart, Al (2020) (in en). Beyond the Basic Stuff with Python: Best Practices for Writing Clean Code. No Starch Press. p. 322. ISBN 978-1-59327-966-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=7GUKEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA322. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ↑ "The Python Language Reference, section 3.3. New-style and classic classes, for release 2.7.1". https://docs.python.org/reference/datamodel.html#new-style-and-classic-classes.

- ↑ "PEP 484 – Type Hints | peps.python.org". https://peps.python.org/pep-0484/.

- ↑ "typing — Support for type hints". Python Software Foundation. https://docs.python.org/3/library/typing.html.

- ↑ "mypy – Optional Static Typing for Python". http://mypy-lang.org/.

- ↑ "Introduction". https://mypyc.readthedocs.io/en/latest/introduction.html.

- ↑ "15. Floating Point Arithmetic: Issues and Limitations – Python 3.8.3 documentation". https://docs.python.org/3.8/tutorial/floatingpoint.html#representation-error. "Almost all machines today (November 2000) use IEEE-754 floating point arithmetic, and almost all platforms map Python floats to IEEE-754 "double precision"."

- ↑ Zadka, Moshe; van Rossum, Guido (11 March 2001). "PEP 237 – Unifying Long Integers and Integers". Python Enhancement Proposals. Python Software Foundation. https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0237/.

- ↑ "Built-in Types". https://docs.python.org/3/library/stdtypes.html#typesseq-range.

- ↑ "PEP 465 – A dedicated infix operator for matrix multiplication". python.org. https://legacy.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0465/.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 Zadka, Moshe; van Rossum, Guido (11 March 2001). "PEP 238 – Changing the Division Operator". Python Enhancement Proposals. Python Software Foundation. https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0238/.

- ↑ "Why Python's Integer Division Floors". 24 August 2010. https://python-history.blogspot.com/2010/08/why-pythons-integer-division-floors.html.

- ↑ "round", The Python standard library, release 3.2, §2: Built-in functions, https://docs.python.org/py3k/library/functions.html#round, retrieved 14 August 2011

- ↑ "round", The Python standard library, release 2.7, §2: Built-in functions, https://docs.python.org/library/functions.html#round, retrieved 14 August 2011

- ↑ Beazley, David M. (2009). Python Essential Reference (4th ed.). Addison-Wesley Professional. p. 66. ISBN 9780672329784. https://archive.org/details/pythonessentialr00beaz_036.

- ↑ Kernighan, Brian W.; Ritchie, Dennis M. (1988). The C Programming Language (2nd ed.). p. 206.

- ↑ Batista, Facundo. "PEP 0327 – Decimal Data Type". https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0327/.

- ↑ "What's New in Python 2.6 – Python v2.6.9 documentation". https://docs.python.org/2.6/whatsnew/2.6.html.

- ↑ "10 Reasons Python Rocks for Research (And a Few Reasons it Doesn't) – Hoyt Koepke". https://www.stat.washington.edu/~hoytak/blog/whypython.html.

- ↑ Shell, Scott (17 June 2014). "An introduction to Python for scientific computing". https://engineering.ucsb.edu/~shell/che210d/python.pdf.

- ↑ Piotrowski, Przemyslaw (July 2006). "Build a Rapid Web Development Environment for Python Server Pages and Oracle". Oracle Technology Network. Oracle. http://www.oracle.com/technetwork/articles/piotrowski-pythoncore-084049.html.

- ↑ Batista, Facundo (17 October 2003). "PEP 327 – Decimal Data Type". Python Enhancement Proposals. Python Software Foundation. https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0327/.

- ↑ Eby, Phillip J. (7 December 2003). "PEP 333 – Python Web Server Gateway Interface v1.0". Python Enhancement Proposals. Python Software Foundation. https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0333/.

- ↑ "Modulecounts". 2022-11-14. http://www.modulecounts.com/.

- ↑ Enthought, Canopy. "Canopy". https://www.enthought.com/products/canopy/.

- ↑ "PEP 7 – Style Guide for C Code | peps.python.org". https://peps.python.org/pep-0007/.

- ↑ "4. Building C and C++ Extensions – Python 3.9.2 documentation". https://docs.python.org/3/extending/building.html.

- ↑ van Rossum, Guido (5 June 2001). "PEP 7 – Style Guide for C Code". Python Enhancement Proposals. Python Software Foundation. https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0007/.

- ↑ "CPython byte code". Docs.python.org. https://docs.python.org/3/library/dis.html#python-bytecode-instructions.

- ↑ "Python 2.5 internals". http://www.troeger.eu/teaching/pythonvm08.pdf.

- ↑ "Changelog – Python 3.9.0 documentation". https://docs.python.org/release/3.9.0/whatsnew/changelog.html#changelog.

- ↑ "Download Python" (in en). https://www.python.org/downloads/release/python-391.

- ↑ "history [vmspython"]. https://www.vmspython.org/doku.php?id=history.

- ↑ "An Interview with Guido van Rossum". Oreilly.com. http://www.oreilly.com/pub/a/oreilly/frank/rossum_1099.html.

- ↑ "Download Python for Other Platforms" (in en). https://www.python.org/download/other/.

- ↑ "PyPy compatibility". Pypy.org. https://pypy.org/compat.html.

- ↑ Team, The PyPy (2019-12-28). "Download and Install" (in en). https://www.pypy.org/download.html.

- ↑ "speed comparison between CPython and Pypy". Speed.pypy.org. https://speed.pypy.org/.

- ↑ "Application-level Stackless features – PyPy 2.0.2 documentation". Doc.pypy.org. http://doc.pypy.org/en/latest/stackless.html.

- ↑ "Python-for-EV3" (in en). https://education.lego.com/en-us/support/mindstorms-ev3/python-for-ev3.

- ↑ Yegulalp, Serdar (29 October 2020). "Pyston returns from the dead to speed Python". https://www.infoworld.com/article/3587591/pyston-returns-from-the-dead-to-speed-python.html.

- ↑ "cinder: Instagram's performance-oriented fork of CPython." (in en). https://github.com/facebookincubator/cinder.

- ↑ Aroca, Rafael (2021-08-07). "Snek Lang: feels like Python on Arduinos" (in en). https://rafaelaroca.wordpress.com/2021/08/07/snek-lang-feels-like-python-on-arduinos/.

- ↑ Aufranc (CNXSoft), Jean-Luc (2020-01-16). "Snekboard Controls LEGO Power Functions with CircuitPython or Snek Programming Languages (Crowdfunding) - CNX Software" (in en-US). https://www.cnx-software.com/2020/01/16/snekboard-controls-lego-power-functions-with-circuitpython-or-snek-programming-languages/.

- ↑ Kennedy (@mkennedy), Michael. "Ready to find out if you're git famous?" (in en-US). https://pythonbytes.fm/episodes/show/187/ready-to-find-out-if-youre-git-famous.

- ↑ Packard, Keith (2022-12-20). "The Snek Programming Language: A Python-inspired Embedded Computing Language". https://sneklang.org/doc/snek.pdf.

- ↑ "Plans for optimizing Python". Google Project Hosting. 15 December 2009. https://code.google.com/p/unladen-swallow/wiki/ProjectPlan.

- ↑ "Python on the Nokia N900". 29 April 2010. http://www.stochasticgeometry.ie/2010/04/29/python-on-the-nokia-n900/.

- ↑ "Brython". https://brython.info/.

- ↑ "Transcrypt – Python in the browser" (in en). https://www.transcrypt.org.

- ↑ "Transcrypt: Anatomy of a Python to JavaScript Compiler". https://www.infoq.com/articles/transcrypt-python-javascript-compiler/.

- ↑ "Codon: Differences with Python". https://docs.exaloop.io/codon/general/differences.

- ↑ Lawson, Loraine (2023-03-14). "MIT-Created Compiler Speeds up Python Code" (in en-US). https://thenewstack.io/mit-created-compiler-speeds-up-python-code/.

- ↑ "Nuitka Home | Nuitka Home" (in en). http://nuitka.net/.

- ↑ Guelton, Serge; Brunet, Pierrick; Amini, Mehdi; Merlini, Adrien; Corbillon, Xavier; Raynaud, Alan (16 March 2015). "Pythran: enabling static optimization of scientific Python programs". Computational Science & Discovery (IOP Publishing) 8 (1): 014001. doi:10.1088/1749-4680/8/1/014001. ISSN 1749-4699. Bibcode: 2015CS&D....8a4001G.

- ↑ "The Python → 11l → C++ transpiler". https://11l-lang.org/transpiler.

- ↑ "google/grumpy". 10 April 2020. https://github.com/google/grumpy.

- ↑ "Projects". https://opensource.google/projects/.

- ↑ Francisco, Thomas Claburn in San. "Google's Grumpy code makes Python Go". https://www.theregister.com/2017/01/05/googles_grumpy_makes_python_go/.

- ↑ "GitHub – IronLanguages/ironpython3: Implementation of Python 3.x for .NET Framework that is built on top of the Dynamic Language Runtime". https://github.com/IronLanguages/ironpython3.

- ↑ "IronPython.net /". https://ironpython.net/.

- ↑ "Jython FAQ". https://www.jython.org/jython-old-sites/archive/22/userfaq.html.

- ↑ Murri, Riccardo (2013). "Performance of Python runtimes on a non-numeric scientific code". European Conference on Python in Science (EuroSciPy). Bibcode: 2014arXiv1404.6388M.

- ↑ "The Computer Language Benchmarks Game". https://benchmarksgame-team.pages.debian.net/benchmarksgame/fastest/python.html.

- ↑ 165.0 165.1 Warsaw, Barry; Hylton, Jeremy; Goodger, David (13 June 2000). "PEP 1 – PEP Purpose and Guidelines". Python Enhancement Proposals. Python Software Foundation. https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0001/.

- ↑ "PEP 8 – Style Guide for Python Code". https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0008/.

- ↑ Cannon, Brett. "Guido, Some Guys, and a Mailing List: How Python is Developed". python.org. Python Software Foundation. https://www.python.org/dev/intro/.

- ↑ "Moving Python's bugs to GitHub [LWN.net]". https://lwn.net/Articles/885854/.

- ↑ "Python Developer's Guide – Python Developer's Guide". https://devguide.python.org/.

- ↑ Hughes, Owen (2021-05-24). "Programming languages: Why Python 4.0 might never arrive, according to its creator" (in en-US). https://www.techrepublic.com/article/programming-languages-why-python-4-0-will-probably-never-arrive-according-to-its-creator/.

- ↑ "PEP 602 – Annual Release Cycle for Python" (in en). https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0602/.

- ↑ "Changing the Python release cadence [LWN.net"]. https://lwn.net/Articles/802777/.

- ↑ Norwitz, Neal (8 April 2002). "[Python-Dev] Release Schedules (was Stability & change)". https://mail.python.org/pipermail/python-dev/2002-April/022739.html.

- ↑ 174.0 174.1 Aahz; Baxter, Anthony (15 March 2001). "PEP 6 – Bug Fix Releases". Python Enhancement Proposals. Python Software Foundation. https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0006/.

- ↑ "Python Buildbot". Python Developer's Guide. Python Software Foundation. https://www.python.org/dev/buildbot/.

- ↑ "1. Extending Python with C or C++ – Python 3.9.1 documentation". https://docs.python.org/3/extending/extending.html.

- ↑ "PEP 623 – Remove wstr from Unicode" (in en). https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0623/.

- ↑ "PEP 634 – Structural Pattern Matching: Specification" (in en). https://www.python.org/dev/peps/pep-0634/.

- ↑ "Documentation Tools" (in en). https://wiki.python.org/moin/DocumentationTools.

- ↑ 180.0 180.1 "Whetting Your Appetite". The Python Tutorial. Python Software Foundation. https://docs.python.org/tutorial/appetite.html.

- ↑ "In Python, should I use else after a return in an if block?". Stack Overflow. Stack Exchange. 17 February 2011. https://stackoverflow.com/questions/5033906/in-python-should-i-use-else-after-a-return-in-an-if-block.

- ↑ Lutz, Mark (2009) (in en). Learning Python: Powerful Object-Oriented Programming. O'Reilly Media, Inc.. p. 17. ISBN 9781449379322. https://books.google.com/books?id=1HxWGezDZcgC&pg=PA17. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ↑ Fehily, Chris (2002) (in en). Python. Peachpit Press. p. xv. ISBN 9780201748840. https://books.google.com/books?id=carqdIdfVlYC&pg=PR15. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ↑ Lubanovic, Bill (2014). Introducing Python. Sebastopol, CA : O'Reilly Media. p. 305. ISBN 978-1-4493-5936-2. http://archive.org/details/introducingpytho0000luba. Retrieved 2023-07-31.

- ↑ Blake, Troy (2021-01-18). "TIOBE Index for January 2021" (in en). https://seniordba.wordpress.com/2021/01/18/tiobe-index-for-january-2021/.

- ↑ Prechelt, Lutz (14 March 2000). "An empirical comparison of C, C++, Java, Perl, Python, Rexx, and Tcl". http://page.mi.fu-berlin.de/prechelt/Biblio/jccpprt_computer2000.pdf.

- ↑ "Quotes about Python". Python Software Foundation. https://www.python.org/about/quotes/.

- ↑ "Organizations Using Python". Python Software Foundation. https://wiki.python.org/moin/OrganizationsUsingPython.

- ↑ "Python : the holy grail of programming". CERN Bulletin (CERN Publications) (31/2006). 31 July 2006. http://cdsweb.cern.ch/journal/CERNBulletin/2006/31/News%20Articles/974627?ln=en. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ↑ Shafer, Daniel G. (17 January 2003). "Python Streamlines Space Shuttle Mission Design". Python Software Foundation. https://www.python.org/about/success/usa/.

- ↑ "Tornado: Facebook's Real-Time Web Framework for Python – Facebook for Developers" (in en-US). https://developers.facebook.com/blog/post/301.

- ↑ "What Powers Instagram: Hundreds of Instances, Dozens of Technologies". Instagram Engineering. 11 December 2016. https://instagram-engineering.com/what-powers-instagram-hundreds-of-instances-dozens-of-technologies-adf2e22da2ad.

- ↑ "How we use Python at Spotify" (in en-US). 20 March 2013. https://labs.spotify.com/2013/03/20/how-we-use-python-at-spotify/.

- ↑ Fortenberry, Tim (17 January 2003). "Industrial Light & Magic Runs on Python". Python Software Foundation. https://www.python.org/about/success/ilm/.

- ↑ Taft, Darryl K. (5 March 2007). "Python Slithers into Systems". eWeek.com. Ziff Davis Holdings. http://www.eweek.com/c/a/Application-Development/Python-Slithers-into-Systems/.

- ↑ GitHub – reddit-archive/reddit: historical code from reddit.com., The Reddit Archives, https://github.com/reddit-archive/reddit, retrieved 20 March 2019

- ↑ "Usage statistics and market share of Python for websites". 2012. http://w3techs.com/technologies/details/pl-python/all/all.

- ↑ Oliphant, Travis (2007). "Python for Scientific Computing". Computing in Science and Engineering 9 (3): 10–20. doi:10.1109/MCSE.2007.58. Bibcode: 2007CSE.....9c..10O. https://www.h2desk.com/blog/python-scientific-computing/. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

- ↑ Millman, K. Jarrod; Aivazis, Michael (2011). "Python for Scientists and Engineers". Computing in Science and Engineering 13 (2): 9–12. doi:10.1109/MCSE.2011.36. Bibcode: 2011CSE....13b...9M. http://www.computer.org/csdl/mags/cs/2011/02/mcs2011020009.html. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- ↑ Science education with SageMath, Innovative Computing in Science Education, http://visual.icse.us.edu.pl/methodology/why_Sage.html, retrieved 22 April 2019

- ↑ "OpenCV: OpenCV-Python Tutorials". https://docs.opencv.org/3.4.9/d6/d00/tutorial_py_root.html.

- ↑ Dean, Jeff; Monga, Rajat; Ghemawat, Sanjay (9 November 2015). "TensorFlow: Large-scale machine learning on heterogeneous systems". Google Research. http://download.tensorflow.org/paper/whitepaper2015.pdf.

- ↑ Piatetsky, Gregory. "Python eats away at R: Top Software for Analytics, Data Science, Machine Learning in 2018: Trends and Analysis". https://www.kdnuggets.com/2018/05/poll-tools-analytics-data-science-machine-learning-results.html/2.

- ↑ "Who is using scikit-learn? – scikit-learn 0.20.1 documentation". https://scikit-learn.org/stable/testimonials/testimonials.html.

- ↑ Jouppi, Norm. "Google supercharges machine learning tasks with TPU custom chip". https://cloudplatform.googleblog.com/2016/05/Google-supercharges-machine-learning-tasks-with-custom-chip.html.

- ↑ "Natural Language Toolkit – NLTK 3.5b1 documentation". http://www.nltk.org/.

- ↑ "Tkinter — Python interface to TCL/Tk". https://docs.python.org/3/library/tkinter.html.

- ↑ "Python Tkinter Tutorial". 3 June 2020. https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/python-tkinter-tutorial/.

- ↑ "Installers for GIMP for Windows – Frequently Asked Questions". 26 July 2013. http://gimp-win.sourceforge.net/faq.html.

- ↑ "jasc psp9components". http://www.jasc.com/support/customercare/articles/psp9components.asp.

- ↑ "About getting started with writing geoprocessing scripts". ArcGIS Desktop Help 9.2. Environmental Systems Research Institute. 17 November 2006. http://webhelp.esri.com/arcgisdesktop/9.2/index.cfm?TopicName=About_getting_started_with_writing_geoprocessing_scripts.

- ↑ CCP porkbelly (24 August 2010). "Stackless Python 2.7". EVE Community Dev Blogs. CCP Games. http://community.eveonline.com/news/dev-blogs/stackless-python-2.7/. "As you may know, EVE has at its core the programming language known as Stackless Python."

- ↑ Caudill, Barry (20 September 2005). "Modding Sid Meier's Civilization IV". Sid Meier's Civilization IV Developer Blog. Firaxis Games. http://www.2kgames.com/civ4/blog_03.htm. "we created three levels of tools ... The next level offers Python and XML support, letting modders with more experience manipulate the game world and everything in it."

- ↑ "Python Language Guide (v1.0)". Google Documents List Data API v1.0. https://code.google.com/apis/documents/docs/1.0/developers_guide_python.html.